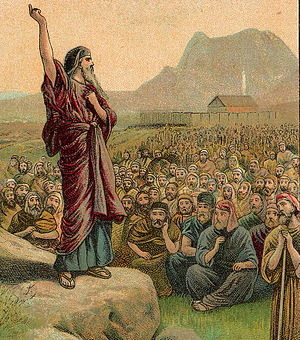

"Sanctify unto me all the firstborn, whatsoever openeth the womb among the children of Israel, both of man and of beast: it is mine."Once again God is stating the first born were his, and which he reserved to himself, to his own use and service; and the people of Israel were under great obligation to devote them to him, since he had spared all their firstborn, when all the firstborn of the Egyptians, both man and beast, were destroyed. The command is addressed to Moses. It was to declare the will of God that all firstborn were to be consecrated to Him, set apart from all other creatures. The command is expressly based upon the Passover. The firstborn exempt from the destruction became in a new and special sense the exclusive property of the Lord: the firstborn of man as His ministers, the firstborn of cattle as victims. In lieu of the firstborn of men the Levites were devoted to the temple services.

Here is an interesting analysis from Presbyterian minister Matthew Henry's (18 October 1662 – 22 June 1714) Concise Commentary on the Bible

In remembrance of the destruction of the first-born of Egypt, both of man and of beast, and the deliverance of the Israelites out of bondage, the first-born males of the Israelites were set apart to the Lord. By this was set before them, that their lives were preserved through the ransom of the atonement, which in due time was to be made for sin. They were also to consider their lives, thus ransomed from death, as now to be consecrated to the service of God. The parents were not to look upon themselves as having any right in their first-born, till they solemnly presented them to God, and allowed his title to them. That which is, by special mercy, spared to us, should be applied to God's honour; at least, some grateful acknowledgment, in works of piety and charity, should be made. The remembrance of their coming out of Egypt must be kept up every year. The day of Christ's resurrection is to be remembered, for in it we were raised up with Christ out of death's house of bondage. The Scripture tells us not expressly what day of the year Christ rose, but it states particularly what day of the week it was; as the more valuable deliverance, it should be remembered weekly. The Israelites must keep the feast of unleavened bread. Under the gospel, we must not only remember Christ, but observe his holy supper. Do this in remembrance of him. Also care must be taken to teach children the knowledge of God. Here is an old law for catechising. It is of great use to acquaint children betimes with the histories of the Bible. And those who have God's law in their heart should have it in their mouth, and often speak of it, to affect themselves, and to teach others.